Rabbi, I have a problem ?

God’s apparent absence during the Holocaust is just one, albeit overwhelmingly powerful, example of what philosophers call the problem of theodicy. Theodicy is the result of our inability to square three traditional assertions about God; that God is omnipotent (all-powerful), omniscient (all-seeing) and omnipresent (all-present).

If God was all-powerful but not always aware of what was going on in our world, He could not be implicated when tragedy strikes. Likewise, if He was all-knowing but not all powerful, He would be beyond reproach, as it would not be in His power to intervene.

Some theologians (process theologians in particular) are comfortable with a God that is not all-powerful and for them the problem of theodicy is less acute. Those who hold to the more traditional Jewish belief in a God who possesses the three “omnis” are left with a serious theological problem when He does not intervene to save the innocent from impending disaster.

A crude solution to the problem of theodicy is to say that the suffering innocent are really not innocent. That their suffering is a punishment from God as justified retribution for sins committed. If ever an event in history proved the fallacy of this argument, it is the Holocaust. It is simply not possible to assert that the six million (among whom were a million and a half children) were sinners.

There are numerous other attempts at trying to explain away the theological problems posed by the Holocaust and they are too numerous to cite here. Suffice it to say they all fall short and many are outright offensive.

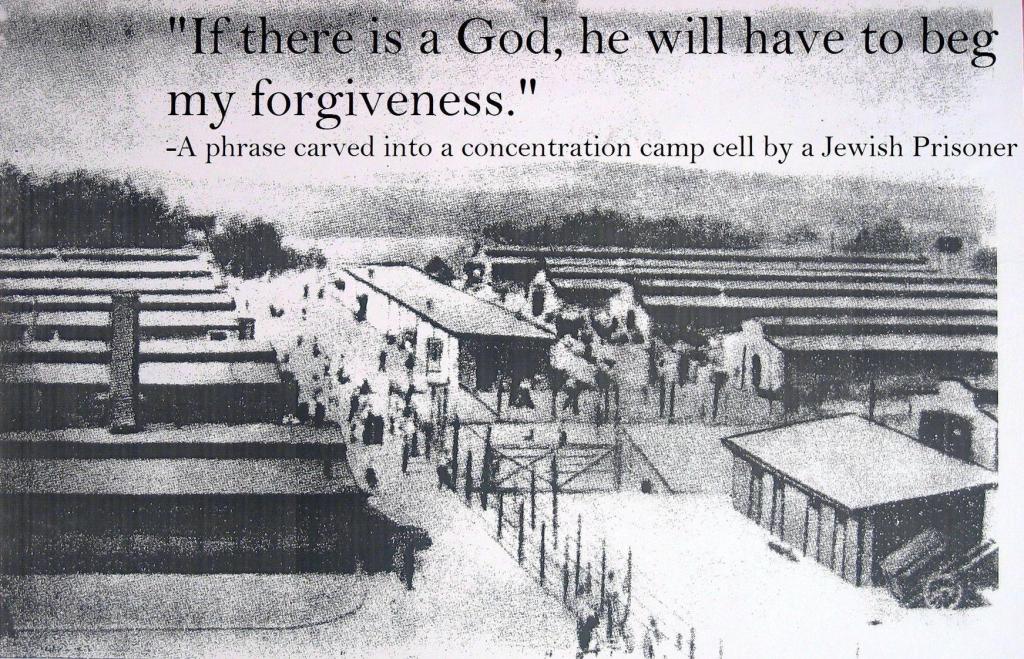

What we are left with is a burning question for which there is no satisfactory answer.

Does this mean that God does not care about us? I hardly think so. The miraculous birth of the state of Israel a few short years after the Holocaust indicates otherwise. I am not suggesting for a moment that the foundation of the state of Israel justifies the Holocaust. It most certainly does not.

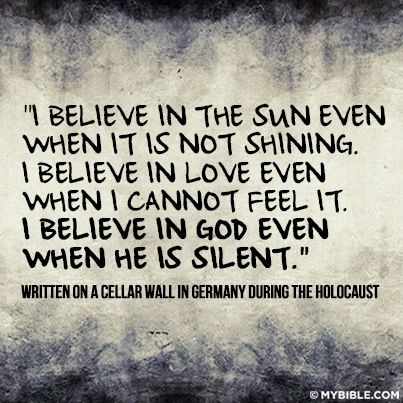

But it does throw into question the easy assertion that God does not care about us. Life is a mystery. It contains blessing and tragedy, joy and pain, light and darkness. Just because we are unable to sense God’s manifestation in the darkness should not lead us to dismiss His presence in times of illumination.

You are right; some people find it problematic reading passages that declare God answers prayer, when we know that many have prayed for help without response, be it in the Holocaust or in recent tragedies, ranging from terrorist attacks to local earthquakes.

Equally difficult are prayers praising God’s care for those who, on the contrary, have had a terrible year, with cancer or bereavements blighting their lives.

But such prayers still have a role, and although you personally may not find satisfactory all of the following very different reasons, perhaps one will appeal to you. The first is that the prayerbook is for everyone: believers, doubters, the hurt, the content, the angry and many more.

Thus prayers which grate with some people will resonate with others and the liturgy has to have a wide range of passages, reflecting the different Jews who read them. Some will indeed feel they have been cared for or rescued, be it in recent times or during the Holocaust, and will gladly utter such words.

Second, the liturgy can be seen as aspirational; it is Godly or goodly (as in the ata gibor in the Amidah) to support the falling, heal the sick and free prisoners. The prayers remind us what we should be doing and act as a moral checklist for our own lives.

Third, talk of God’s care can be in pastoral terms rather than practical ones. People may endure hardships, but still feel loved by God and that sense of relationship helps them carry on, rather than give up in despair.

Fourth, by contrast, some view God as not having a personal role or intervening in individual lives, but being the power behind Creation. This may entail letting go of a long-held image, but is seen as more realistic. It means we pray to God to help us develop our own inner qualities, such as patience or courage, rather than changing external events in our favour.

Your point is also a good argument for updating the liturgy, so that it speaks to those with religious question marks. Thus the new Reform machzor has passages referring to the difficulty of understanding God or our place in the world and admitting that some issues can be hard to resolve.

Coming to High Holy Day services does not mean having all the answers, but reckoning that the search is worthwhile.